Christianity, Citizenship, and American Empire in the Korean War

by Sandra H. Park

“As you read…you will thrill with many at the power of our God to change a rank Communist into a glorious Christian.” Thus proclaimed Billy Graham in his introduction to Harold Voelkel’s account of the POW ministry during the Korean War (1950-1953) shortly after the armistice signing. The “rank” Communists were the captured North Korean soldiers who refused to return to North Korea because they found Christ in the camps, Voelkel and Graham claimed. Instead, these POWs became citizens of “free” South Korea, scoring for the United States and South Korea a moral victory after their failed attempt to “roll back” communism. This story of freedom and triumph, however, masks a complicated relationship between religion, citizenship, and American empire in Korea.

In Faking Liberties, Jolyon Baraka Thomas exposes the fraudulence of US American occupiers’ claim of authoring authentic religious freedom (and thus, democracy) for a postwar Japan. The Americans invented a totalizing “State Shintō” to argue that the Japanese needed the American gift of religious freedom. During this same time in the United States, K. Healan Gaston’s Imagining Judeo-Christian America traces a crescendo of voices that theorized “Judeo-Christianity” as the foundation of US democracy and a spiritual weapon against godless communism. These seemingly contradictory imperialistic and nationalist claims about religion, freedom, and democracy had implications for the US project in Korea as well.

At the same time that it occupied Japan, the US occupied Korea and claimed to introduce a new arrangement of religion and politics for Koreans. In August 1945, Japan’s defeat in the Pacific War ended its 35-year colonial rule in Korea. The US, however, unilaterally divided Korea at the 38th parallel and dispatched a military government to occupy—“liberate”—the south from 1945 to 1948. One aspect of this liberation centered on compulsory Shintō shrine attendance during Japan’s wartime mobilization (1937-1945). With the arrival of US occupiers, Koreans, especially Christians, were now supposedly free from Japan’s state religion. However, the US mobilization of South Korea against the new enemy—communism—gave shape to a relationship between “religion” and “citizenship” that resembled the colonial arrangement more than US policymakers, missionaries, and Korean Christians cared to admit.

During the Korean War, the American narrative over its intervention in Korea—as standard-bearers of freedom against the vanquished colonizers of the old and growing threat of global communism—harmonized with the “conversion” narratives of North Korean POWs. Following the US-led Inchon landing in September 1950, the UN captured and interned over 170,000 POWs (including around 21,000 Chinese POWs). In these camps, North Korean prisoners, white American missionaries, South Korean Christian leaders, and even state officials began to articulate Christian conversion as a pledge of allegiance for South Korean citizenship.

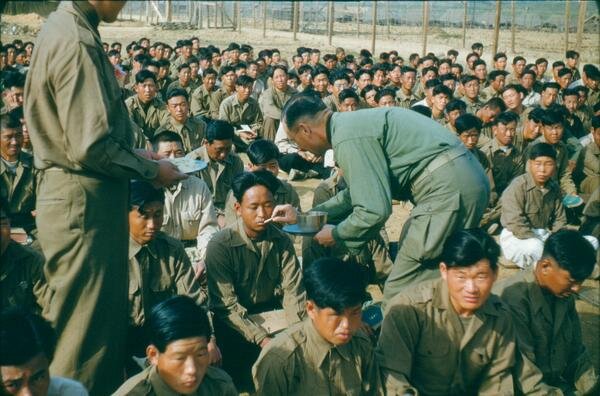

Between early 1951 and July 1953, thousands of POWs encountered Christian evangelism through the Department of Army Civilian (DAC) POW ministry. While a few other Protestant and Catholic missionaries were employed, Harold Voelkel (PCUSA) stood at the helm of the project. A veteran Presbyterian missionary to Korea since 1929, Voelkel spoke Korean proficiently. For Voelkel, what began as a “fine evangelistic opportunity” to proselytize isolated clusters of Communist POWs in the early months of the war turned into near-daily evangelical work in the UN POW camps (Figure 1). Over two and a half years, Voelkel not only held regular Protestant worship services but also ministered Holy Communion and baptism to prisoners (Figure 2).

Figure 1: North Korean POWs Singing Hymns at Nonsan Camp

Figure 2: Baptism. Source: Presbyterian Historical Society, SLIDES B84 (41).

One POW who encountered Voelkel’s ministry is Chang Sik Kim, now a published theologian. For Kim, the prospect of mandatory repatriation caused him to fear persecution by the North Korean state for his Christian faith. But something revelatory happened in the camps. Kim experienced the power of Christ’s blood to transform wartime circumstances when he and fellow prisoners wrote petitions in their own blood to protest repatriation (Figure 3). In A Theology of the Blood of Jesus Christ (2010), Kim recollected that Voelkel, on seeing the prisoners fainting from the loss of blood, wept and took the blood petitions to South Korean president Syngman Rhee (Figure 4). While other concerns more forcibly drove Washington and Seoul to pursue a voluntary repatriation policy against protests of foul play from Pyongyang and Beijing, Kim theorized that the power of his mere blood to secure the intercession of Voelkel, and perhaps even Rhee, testifies to the limitless power of the blood of Christ. So, to Kim, intercession from an American missionary, a state leader, and Christ enabled uniformed North Korean enemies to become South Korean citizens.

Figure 3: Blood Petitions. North Korean POWs created “a replica [for Voelkel] of their signatures to a petition declaring they would rather die than be repatriated.” Source: Presbyterian Historical Society, Gal.3 V857.

Figure 4: Syngman Rhee visits anti-Communist POWs, 1952. South Korean president Syngman Rhee waves to North Korean POWs holding South Korean flags behind the camp’s barbed wire. Source: National Archives of Korea.

What emerged out of the Korean War POW camps, then, was a particular pedagogy that folded “citizenship” and “Christianity” into one another. In other words, many North Korean POWs learned to iron out their complex life histories and wartime circumstances (such as why they refused repatriation) into a “genuine” testimony of conversion—to Christianity and anticommunism—as a way to pass South Korea’s wartime citizenship test. Of course, not all of the 30,000 or so North Korean POWs who became South Koreans after the war were Christians. However, the politics of “religious” and “political” conversion in the camps overlapped to such a degree that it is impossible to determine an exact number without applying our own litmus test (e.g., do we count everyone who attended worship services or only those baptized?)

To make some sense of this blurring between religion and citizenship—a charge that, as Thomas reminds us, Americans had laid against Japan—Talal Asad’s remark on modern colonialism is helpful: "although the West contains many faces at home it presents a single face abroad.” In the case of the Korean War and American empire, the many faces at home can refer to what Gaston astutely observes as the linguistic project of “Judeo-Christianity.” This project can be discerned in the regular US Army chaplain corps that ministered to Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish GIs in Korea. The single face presented abroad, on the other hand, was reflected in the DAC POW ministry to convert North Korean prisoners to Christianity, as well as the all-Christian South Korean military chaplaincy created by the US military in early 1951. During the Korean War, many US Americans and Koreans agreed that not any religion (or even solely military force) could safeguard Korea’s frontline against global communism. Only one could do so, and it was Christianity.

Sandra Park is a doctoral candidate in the history department at the University of Chicago. Her dissertation research interrogates the relationship between Christianity, citizenship, and state powers by examining the passage of North Korean refugees and POWs into wartime South Korea. Recently, she has published an article on courtroom debates over the place of religion during the North Korean revolution. Her departmental page can be found here.

![Figure 3: Blood Petitions. North Korean POWs created “a replica [for Voelkel] of their signatures to a petition declaring they would rather die than be repatriated.” Source: Presbyterian Historical Society, Gal.3 V857.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/601deb1d6348a502c3d9ecdb/1613063958503-GIP77V4DMN9IEJYNVZC5/ParkSandra_Figure3+copy.jpg)