Buying and Selling Narratives of Health: Sources and Methods in the Study of the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company

by Sarah Dees

21 July 2023

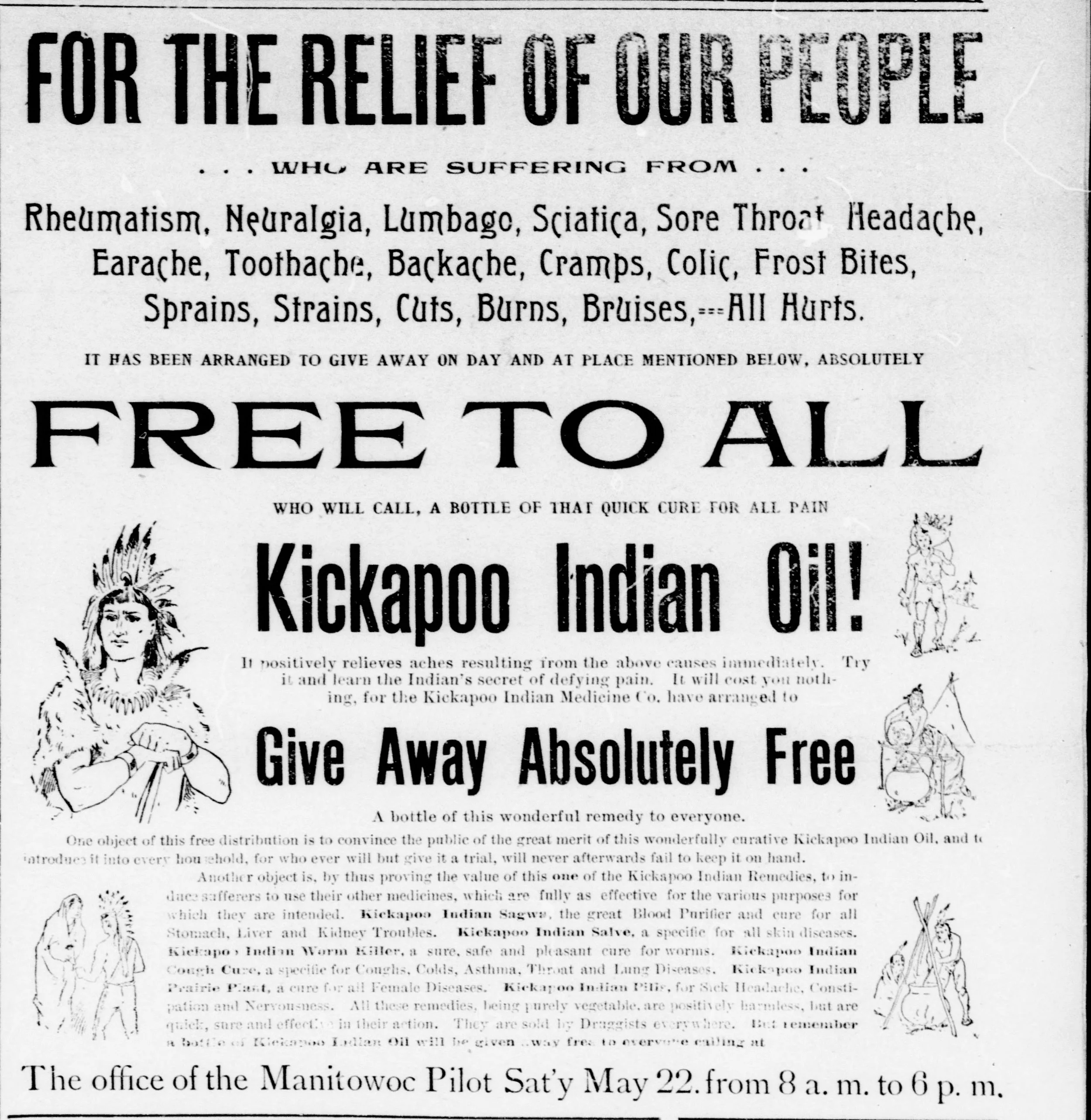

Figure 1: The Wide Reach of Kickapoo Advertisements

While it was based on the East Coast, the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company advertised its medicines throughout the Midwest and West. Identical advertisements appeared throughout the United States.

In the article “Before and Beyond the New Age: Historical Appropriation of Native American Spirituality and Medicine” (American Religion 4.2), I describe the appropriation and commodification of Native American medical and cultural practices in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. The focus of my analysis is the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company, a business that was founded by two white men in the late-nineteenth century. The company purported to sell authentic “Indian medicines,” which they marketed to consumers throughout the United States.

The name of the company was derived from the Kickapoo, a nation of Algonquian-speaking Native North Americans whose original homelands were in the Great Lakes region of what is today the United States. Through migration and forced removal, Kickapoo communities gradually moved south and west as the United States sought to expand its territory. There are now federally-recognized Kickapoo tribal governments in Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas, as well as in Mexico. While they used the name of an existing Native nation, the owners of the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company did not act on behalf of the Kickapoo people themselves. Instead, the company fabricated and furthered stereotypical stories and imagery of Native American communities in order to sell their patent medicines to a broad, non-Native American public.

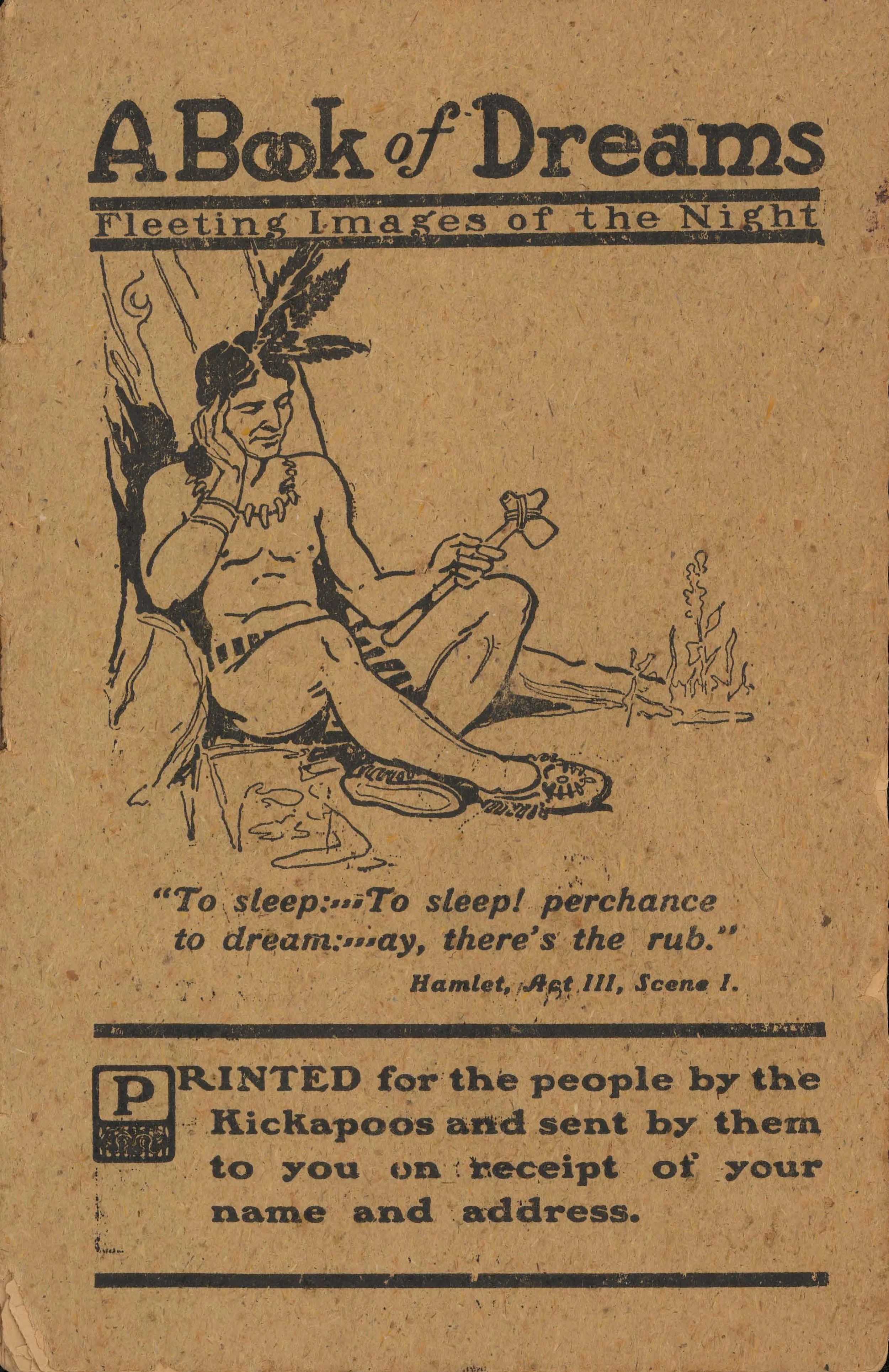

Figure 2: Imitation Indians

“Imitation Indians,” The Mitchell Capital (Mitchell, South Dakota), May 21, 1897, page 10. See full text here.

This essay and accompanying images and files supplement the article with additional context and offer readers access to primary source material. In what follows, I share some thoughts on the process, methods, and sources I used as I researched this company. I highlight some of the key images I analyze in the essay, which are now freely available via the Library of Congress’s database Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. In addition, you will find full-length PDF versions of pamphlets produced by the Kickapoo Indian Medicine company that I collected as I researched this topic.

I am grateful to the work of Mindy McCoy, Preservation Services Coordinator at Iowa State University Library, for her work to digitally preserve the booklet-length pamphlets on this page in a high-quality format so that they can be made more widely available for study. Readers should be aware that the pamphlets contain stereotypical depictions of Indigenous cultures (which my article discusses in more detail).

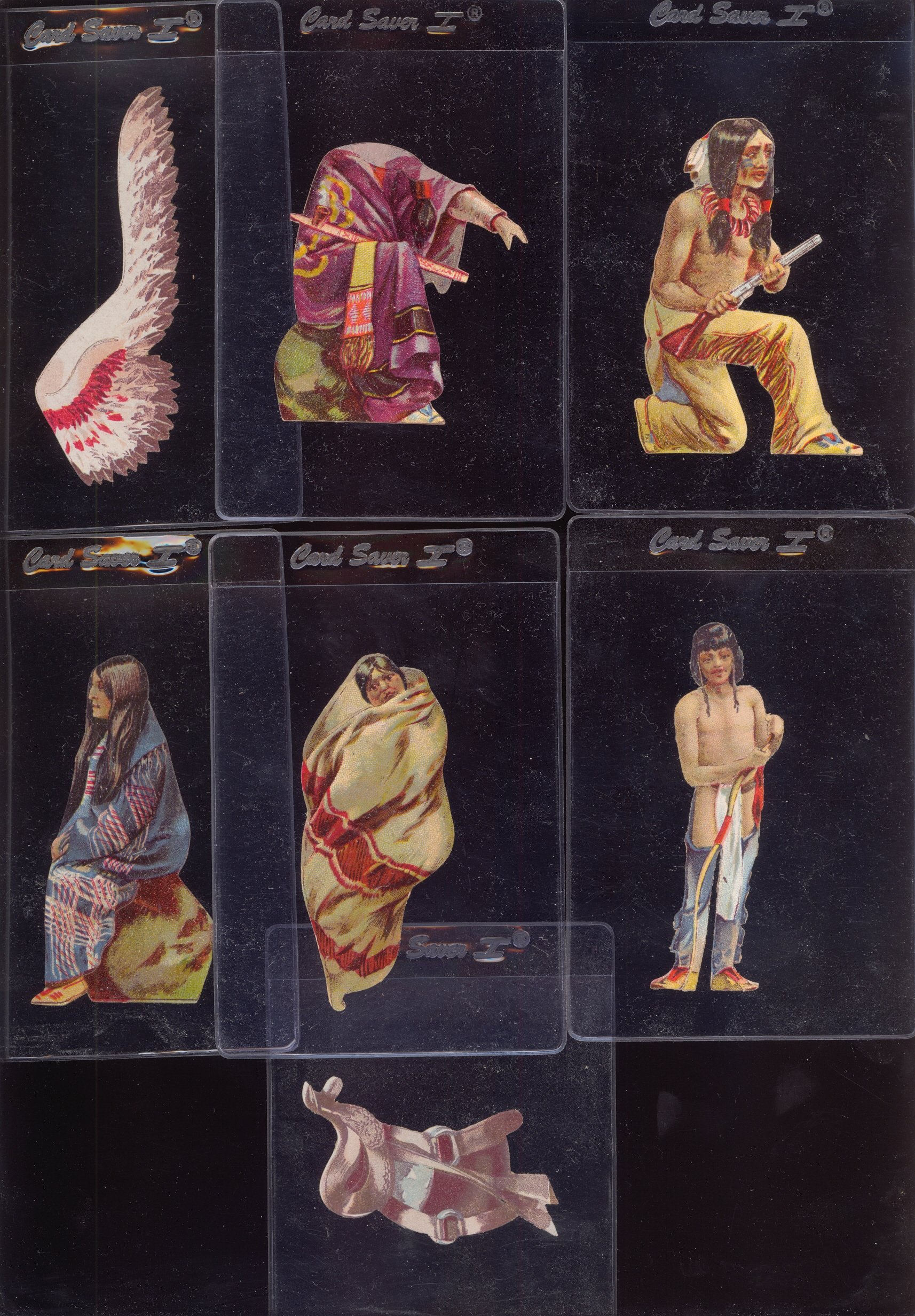

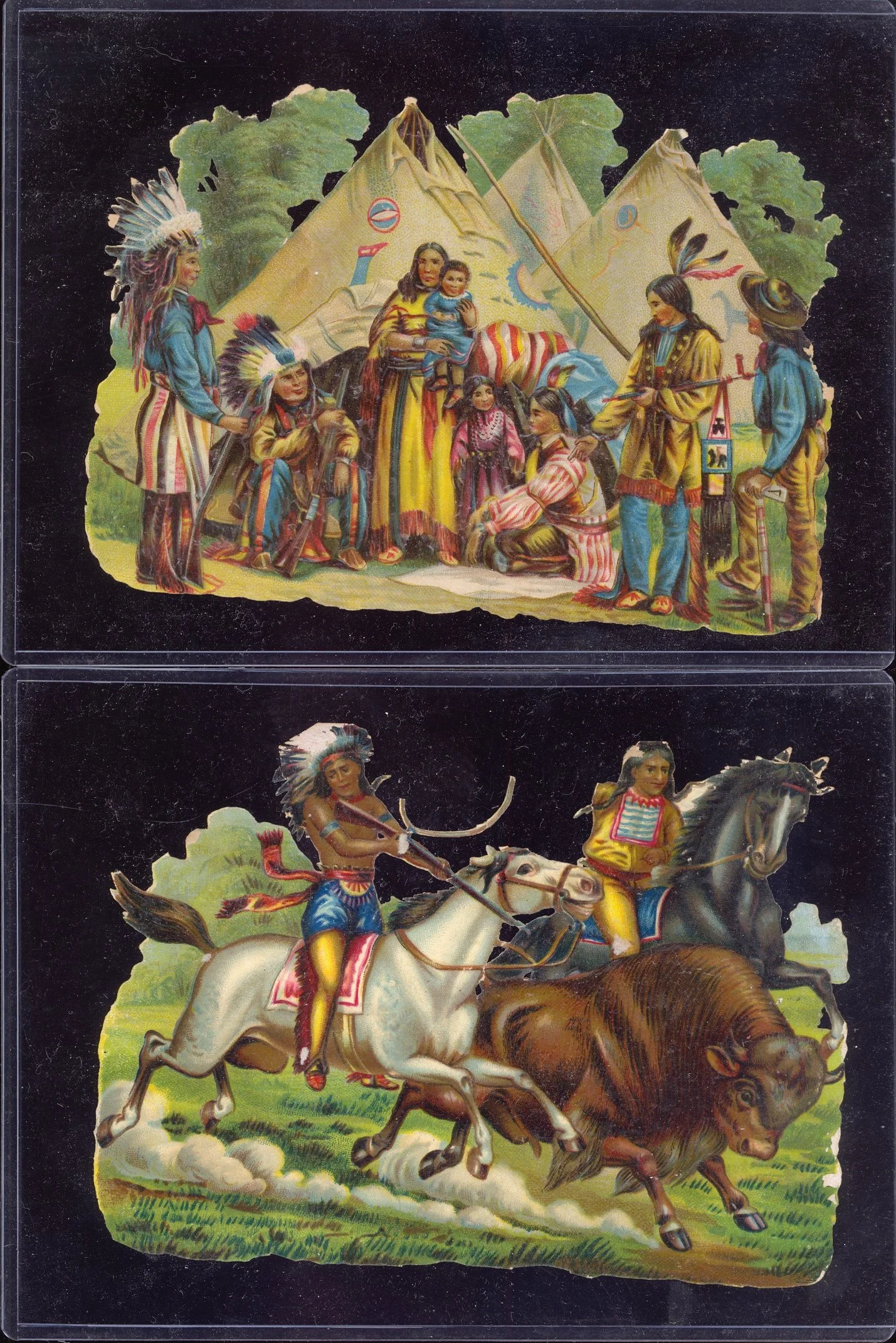

Figure 3-5: Kickapoo Indian Company Paper Dolls

These die cut paper dolls were distributed to consumers to advertise the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company’s many remedies, encouraging consumers to “play Indian.”

Figure 3 (Front)

Figure 4 (Front)

Figure 5 (Front)

Figure 3 (Back)

Figure 4 (Back)

Figure 5 (Back)

Images

My article describes the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company and analyzes the narratives it shaped through its advertisements. One key argument my article advances is that, in addition to economic exploitation, religious appropriation furthers ideological harm through its proliferation of misleading narratives. This occurs when cultural outsiders create and further false accounts of the cultures from which they appropriate, which often serve to justify the exploitation. I show how, in addition to hawking patent medicines or “snake oils,” the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company sold a narrative to its consumers. Through its advertisements, it tried to convince consumers that the white owners of the company—not Native Americans—were the ultimate authorities on Indigenous history, culture, and medicine. Further, the advertisements suggested that Native people were happy to give up their knowledge for cultural outsiders. These advertisements presented a damaging, false narrative about Native American history and culture. They suggested that the benefactors of Indigenous spiritual and medical practices should be non-Natives, rather than Native peoples themselves.

What’s in a name?

The title of my article is a nod to historian Joel Martin’s 1991 article published in the Journal of the American Academy of Religion entitled “Before and Beyond the Ghost Dance: Native American Prophetic Movements and the Study of Religion.” In this article, Martin argues that, among scholars of religion who are not specialists in Indigenous traditions, attention to Native American traditions usually revolves around the Ghost Dance tradition, which was initiated in 1889, and the subsequent massacre of Lakota Ghost Dance practitioners in 1890. Martin argues that, while these topics are important, focusing solely on them—at the expense of other topics—severely limits our understanding of Native American religions. First, Native American prophetic movements have a much longer history. The Ghost Dance is part of a longer set of stories about Indigenous religious innovation and resistance. And second, the story of the Wounded Knee massacre often tends to be fatalistic, suggesting that it was a tragic event that signaled the inevitable decline of Native American religion and spirituality. In reality, Native American religions have continued despite these forms of violence. (Indeed, this narrative of Native religions as relics of the past continues to persist.)

While the topic of my Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company article is obviously distinct from the subject of Martin’s essay, it does take place during the same era, the “assimilation era” of US Federal Indian Policy. This was a devastating era, lasting from roughly 1880 to 1930, in which federal policies targeted nearly all facets of Native American life and culture. In addition, I make a similar point about the persistence of common narratives about Native American religions that don’t tell the full story. Often, scholars point out the New Age tradition, from the 1960s onward, as the primary site of religious appropriation of Indigenous traditions. While appropriation does occur within the New Age tradition, I show that spiritual appropriation happened much earlier than the dawning of the New Age in the mid-twentieth century. Further, I argue that this form of appropriation has occurred among a much larger population than a countercultural group of spiritual outsiders.

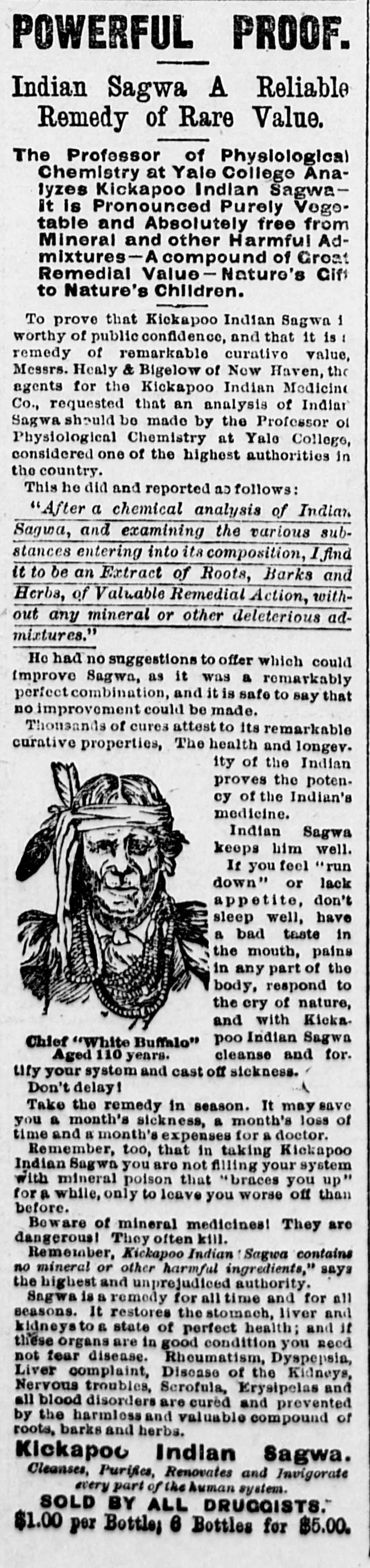

Figure 6: Powerful Proof

“Powerful Proof,” Omaha Daily Bee (Nebraska), July 15, 1893, page 5. See full text here.

Process

This article grew out of seminar papers I wrote at the beginning of my PhD program. During my first semester, I took a class about religion, health, and medicine (a class that I will be teaching for the first time this fall). I was interested in writing my class paper about the New Age appropriation of Native American medical practices. During the course, a “New Age tragedy” occurred when a non-Native spiritual leader tried to create a “sweat lodge” ceremony. James Arthur Ray is a bestselling author and self-help guru whose work on spirituality and wealth has been touted by Oprah Winfrey. In October of 2009, Ray hosted an expensive and exclusive “Spiritual Warrior” retreat near Sedona, Arizona, that was based on an assortment of New Age practices. The “sweat lodge” ceremony during the retreat resulted in the deaths of three participants. (Ray was later convicted of negligent homicide and served two years in prison. After his release, he returned to his self-help business. He currently hosts workshops, courses, and podcasts related to magic, wealth, and redemption. In 2020, he published a book entitled The Business of Redemption: The Price of Leadership in Both Life and Business; the first chapter discusses the disaster at Sedona.) My paper for that course analyzed the harms caused by New Age appropriation of Native American spiritual and medical practices.

I intended to turn to a new topic in a seminar I took the following semester on American Christianity. I initially conceived of a project on historical connections between race, religion, and country music. When the genre of country music was in its infancy in the early twentieth century, before the advent of radio broadcasting technology, long-distance travel was difficult. Traveling performers spread their music—sacred and secular—via entertainment troupes, religious revivals, and minstrel and medicine shows (content warning: link contains an image of white minstrel performers in blackface). I stumbled upon the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company while researching these traveling shows. I initially planned to research the role of music in the shows, but after examining primary sources related to the company, I saw that the issue of medical appropriation was at play during this earlier era. This was in line with what scholars such as Philip J. Deloria have shown: that there has been a long history of non-Native people who appropriate Native American cultural imagery or even “play Indian” by presenting themselves as Native American. After examining the advertising materials, I decided to turn my attention back to the question of religious and medical appropriation—this time from a historical perspective.

Figure 7: Woman’s Hope

“Woman’s Hope,” Vilas County News (Eagle River, Vilas County, Wisconsin), May 17, 1897, page 7. See full text here.

Sources and Methods

After finding references to the company, I searched historical newspapers for primary source material. I ended up finding dozens of advertisements published in newspapers throughout the United States. (See Figure 1: “The Wide Reach of Kickapoo Advertisements.”) I initially used Gale’s Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers database and ProQuest Historical Newspapers database for these newspaper sources. Many advertisements were printed as articles, and these were reproduced in newspapers throughout the US American West and Midwest. While doing searches through my library’s database, I realized that the company had produced brochures and pamphlets. In addition to requesting physical and digital versions of these pamphlets through Interlibrary Loan, I also scoured eBay for copies. In addition to finding pamphlets for sale on eBay, I also found numerous forms of ephemera that Indian medicine companies produced, including paper dolls, postcards, fans, and posters. These documents were distributed for free as advertisements in the past; today, there is a market for these documents. (See Figures 3-5, Die Cuts.)

The conclusions in the article are the product of an inductive textual analysis. I collected advertisements and read through the sources, identifying themes and patterns. My essay highlights two key recurring narratives I noticed in the advertisements: one about authority—who had the authority to create and market the medicines—and the other about who should benefit from these medicines.

Figure 8: A Modern Pocahontas

“A Modern Pocahontas,” Courier Democrat (Langdon, North Dakota), May 6, 1897, page 7. See full text here.

Cultural, Religious, and Medical Supersession

Advertisements suggested that the two company owners had gained secret, authentic Kickapoo medicine recipes. However, the owners had drawn on modern science to perfect the remedies. Thus, they claimed authority over this “authentic” medical knowledge derived from another culture. (See, for example, Figure 2: “Imitation Indians” and Figure 6: “Powerful Proof.”)

A Fantasy of Sacrifice

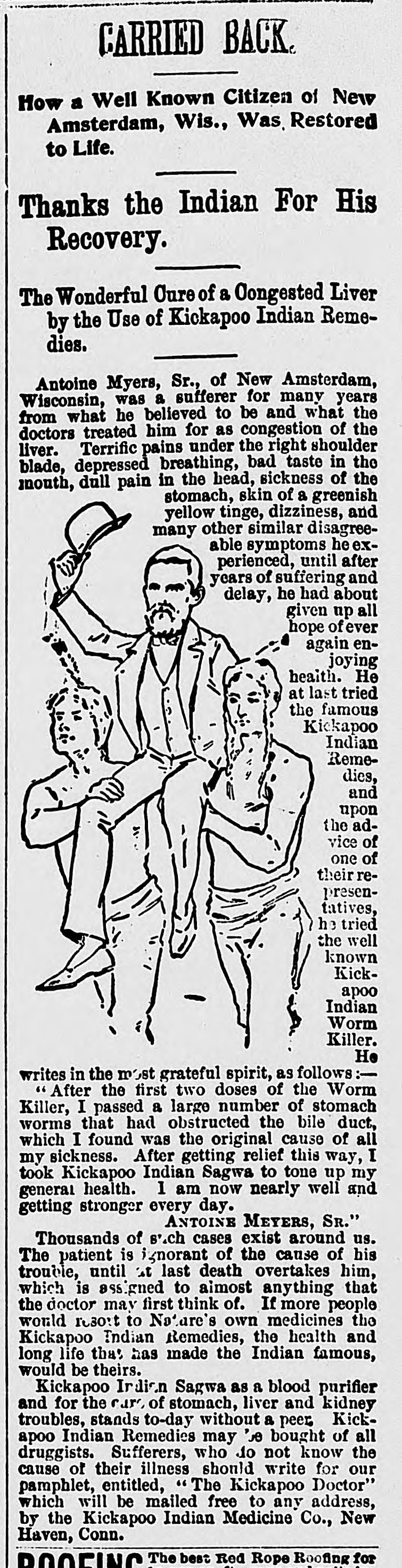

Second, advertisements presented Native American people as willingly sacrificing their knowledge for non-Natives. My article shows how this is at odds with the federal Indian policies of the day, which sought to diminish the influence of Indigenous spiritual leaders and discourage the use of traditional Indigenous healing practices. (See, for example, Figure 7: “Woman’s Hope,” Figure 8: “A Modern Pocahontas,” Figure 9: “Carried Back,” and Figure 10: “From the Jaws of Death.”)

Figure 9: Carried Back

The Washburn Leader (Washburn, North Dakota), November 13, 1897, page 2. See full text here.

Figure 10: From the Jaws of Death

“From the Jaws of Death!,” Little Falls Weekly Transcript (Little Falls, Minnesota), November 12, 1897, page 9. See full text here.

Figure 11: Kickapoo Indian Oil Advertisement

This advertisement highlights the many remedies that the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company peddled. See full text here.