Oil City, Alberta

by Judith Ellen Brunton

Cover Image of Ghost Towns of Alberta by Harold Fryer

On Monday March 30th, 2020, the price of oil from Alberta’s oilsands, dropped dramatically.[1] Due to dynamics of the global oil economy and the effects of Covid-19, Canadian oil was, as the CBC reported, “functionally worthless.” This moment threatened an emptiness that is familiar to people in Alberta, a province dotted with the ghosted towns of former resource-extraction communities. Here, emptiness is not just an absence of lives, but the presence of fear.

The fear that lives in the emptiness of Alberta’s ghost towns and in the emptiness suddenly being spread by Covid felt like kin to me. I study how oil is used allegorically by community organizations, government agencies, and corporations in Alberta to articulate hope, aspiration, and the good life. My fieldwork brought me to Alberta’s Energy Heritage sites, the Calgary Stampede Rodeo, municipal economic development initiatives, and to the Imperial Oil archives. But alongside the atmosphere of optimism these spaces and their narratives promote, oil also has an affect of fear, and as I look towards my next project, I am drawn to ghost towns, disaster sites, and paranormal hunters.

In March, mainstream and social media became occupied with the spectacle of formerly populated spaces standing empty. These empty places became symbols of the change in our lives. As I walked my dog in Toronto in these early Covid days, I often saw people with large cameras clicking away in the middle of an empty street. Empty places seemed to allow these photographers to ritualize the fear that was otherwise unpracticed or invisible. Emptiness — in these freshly-made Covid ghost towns as well as in Albertan ghost towns — is not a rupture of religion as it is lived in North America, but an experience of North American religiosity itself. Emptiness creates a specific space for the rituals, engagement, and storytelling that populate emptiness with both fear and potential.

Examining what is considered empty can enable us to see what values and meanings shape peoples’ worlds. The prospect of vanishing labour is a fear that lives in both Covid emptiness and in Albertan ghost towns. Vanishing is also at the spiritual centre of Harold Fryer’s 1976 paperback Ghost Towns of Alberta. Fryer begins the book with Psalm 103: “The days of man are but as grass: For he flourisheth as a flower of the field. For as soon as the wind goeth over it, it is gone; And the place thereof shall know it no more.” With this framing, Fryer invites readers to travel knowing that they will one day be gone, not even remembered by the place itself. This possibility is familiar to people living and working in Alberta.

The land now called Alberta was part of the Dominion of Canada’s imperial yearnings. After Canada purchased this area from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1869, it negotiated Treaties 6, 7, and 8 with representatives of the First Nations who lived with, cared for, and told stories about this land.[2] The state’s intention with these treaties was to accommodate settlement and make the surface and subsurface rights available for sale. Since then, resource management has been central to the province’s relationship to the rest of the country and its own settlement. This dependency on resource extraction creates the conditions for ambition and hope, but it also shapes a constant quiet fear, one that hides behind the exuberance of hope, bust always shadowing boom.

Map from Ghost Towns of Alberta by Harold Fryer

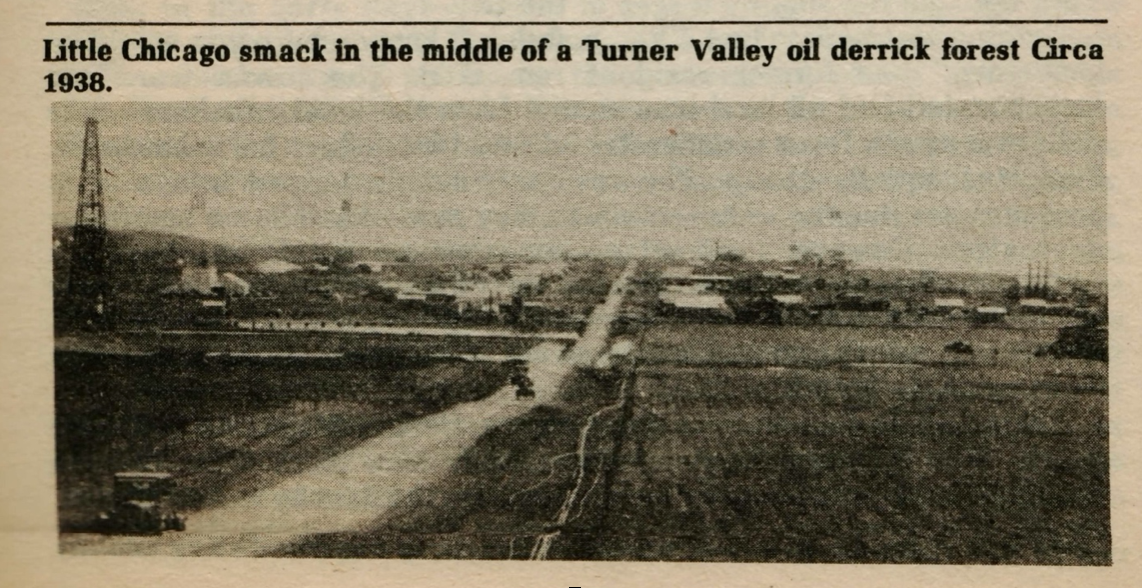

When the price of oil plummeted, I imagined the fear suddenly revealing itself to Albertans, a sudden dark shape behind them in a mirror. Like many places globally, Alberta felt an old fear return stronger, summoned by Covid. But while Covid is new, the boom and bust cycle is not. There are many abandoned places in the province that were formerly essential to resource extraction and transport. In the 1970s, Fryer went from wondering if he “could find enough ghost towns” to being convinced that “there are more places that can be called ghost towns than [he had] dreamed of.” In total he wrote about eighty-one towns. For Fryer, the threat of bust lurked in how these towns boomed, in their magnificence and dynamism. In places like Oil City and Little Chicago, Fryer describes the presence of laboring people extracting resources as signifying life, “crawling with oil people seeking their fortunes.” Emptied of these fortune seekers, Fryer saw the towns as dead. He uses funerary language in describing the town of Coal Valley, saying “...the land still bears evidence of an industry and town that died. A fitting epitaph might well read: COAL VALLEY MINE 1902-1922-1955; TOTAL COAL OUTPUT-5,422,719 TONS; WE COULDN’T COMPETE WITH OIL AND GAS.”

Section of entry on “Oil City” in Ghost Towns of Alberta

Scan of an entry on “Little Chicago” in Ghost Towns of Alberta

“Ghost town” describes a former place, but these are also new places. These former boom towns are visited today as heritage sites, museums, memorials, and curiosities. A CBC article followed a group of “ghost towners” for whom these spaces were both fascinating and meaningful.[3] One individual says there that, “For me, it’s spiritual, as well.” The emptiness of these ghost towns is easily translated into meaning. Like the photographers capturing empty Toronto streets, the Albertan ghost town’s emptiness facilitates an engagement with fear. The emptiness creates space in the present to reflect on the ambitions that founded these towns and to imagine our own potential futures. I felt this way as I pulled off the highway onto a gravel road on the hot summer day when I visited Little Chicago, now a model derrick on a memorial cairn with its fence topped with used drill bits. Only fields and highway in all directions, except for a natural gas flare burning to the west. The fear in this emptiness is Albertan: a fear that all its booming cities will one day be roadside curiosities.

Image of the commemorative area on the site of the former “Little Chicago”

The cairn and commemorative plaque on the site of the former “Little Chicago”

Emptiness provides insight into people’s values and worldviews. It allows us to examine what emptiness entails in different contexts: Empty of whom? Empty of what work? Alberta’s ghost towns are empty because the resource extraction work is gone. But the photographers filled the empty streets of Toronto as I watched them, and the ghost towners visit empty boom towns. In opening his book with Psalm 103, Fryer seems to encourage readers to confront their impermanence without fear. Certainly, the emptiness of ghost towns is only populated by fear if Alberta is tied to a specific understanding of “empty.” What would it mean for Albertans to enter this emptiness without fear? Alberta was not empty before state and corporate forces began extracting resources for profit. It won’t be empty after.

The author beside a dismantled pumpjack in rural Alberta

[1] Pete Evans, “Oil Price Dips below $20 US a Barrel — and Canadian Oilsands Crude Is Almost Worthless” CBC, March 30, 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/oil-price-plummet-monday-1.5514653.

[2] The eleven numbered treaties negotiated by the Crown, the Dominion of Canada on behalf of the British monarch, were signed between 1871 and 1921 and each have unique histories. Treaty Six signatories were representatives of Plains, Wood Cree, Nakota, Saulteaux and Dene bands. Treaty Seven was signed by representatives of five plains First Nations: the Siksika, Kainai, Piikani, Stoney-Nakoda, and Tsuut’ina. And Treaty Eight was signed by representatives of the Cree, Dene Tha’, Danezaa and Denesuline First Nations of the Lesser Slave Lake area. In each case the written treaties and the oral agreements discussed at the treaty signings are not aligned. Treaty conditions were designed to incrementally reduce the amount of land each reserve was allotted. For more on this subject I suggest Sarah Carter’s 1990 text Lost Harvests. For brief information on Canada’s numbered treaties you can visit The Canadian Encyclopedia at https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/numbered-treaties.

[3] Vincent Bonnay, “The Hidden Lives of Alberta’s Ghost Towns,” CBC, August 29, 2020, https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/longform/the-hidden-lives-of-albertas-ghost-towns.

Judith Ellen Brunton is a doctoral candidate at the University of Toronto’s Department for the Study of Religion. Judith is an anthropologist of religion in North America whose current project explores how legacies of oil extraction allow for specific contemporary imaginaries of the good life in Alberta. In this project, Judith follows how oil companies, government agencies, and community organizations in Alberta use oil to describe a specific set of morals and values. This includes case studies on: Imperial Oil’s publications on history and culture, Energy Heritage sites, The Calgary Stampede, and various corporate aspirational initiatives in Calgary. Judith held a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Doctoral Scholarship to pursue her research. She was an Honorary 2019-2020 Louisville Dissertation Fellow and a 2019-2020 Jackman Humanities Institute Graduate Fellow exploring the theme “Strange Weather.”