Speaking Truth in Late Antique Poetry

by Laura S. Lieber

Breviculum ex artibus Raimundi Lulli electum - Cod. St. Peter perg. 92. Miniaturenzyklus über Leben und Lehre des Raimundus Lullus. (Public Domain).

In the thirteenth century, Christian authorities in Europe (Ashkenaz) began to censor the Jewish prayer known as the Aleinu, removing a line they understood to be an anti-Christian slur. The offending line, restored during the post-War period in many prayer books (and never dropped by Italian, Sephardic, and Mizrahi Jews) states: “For they worship vanity and emptiness, and pray to a god who cannot save.” It did not matter to the Christian authorities that these phrases came from the Bible (specifically Isaiah 30:7 and 45:20), or that Jewish folklore of the time attributed the prayer to Joshua at Jericho. In some cases, Jewish communal authorities, anticipating censure, preemptively removed the line themselves; in others, in response to intensifying mutual animosity, Jewish liturgists expanded the prayer in order to make the polemical connotations explicit. Indeed, despite official protestations, some Jews no doubt thought of Christians as they recited the Aleinu—if not before the censorship, then after the censors objected. The words were ancient, but the contexts new and changing.

My research focuses on Jewish and Christian (and also Samaritan) liturgical poetry from Late Antiquity (the period from roughly the third through seventh centuries CE) in the Eastern Mediterranean world. This period witnessed the flourishing of diverse and innovative styles of hymnody. While Jews, Christians, and Samaritans all composed numerous liturgical poems, these works let individuals speak of each other but not to each other. And yet, the words of prayer did shape worldview, whether affirming Jewish truths in the face of Christian false worship or condemning Jews as deicides in the Easter liturgy. But we must remember that while Late Antiquity was hardly an age of tolerance, coexistence was largely the norm. We would err if we saw the period from the Christianization of the Roman Empire to the rise of Islam in the Levant as one of incessant conflict. When it was written, the Aleinu was probably not generally heard as specifically anti-Christian polemic; a few centuries later, any other reading seems implausible.

Dabru Emet speaks predominantly to its authors’ moment in the late twentieth century; its concern is not primarily with history. Indeed, it articulates a vision of interreligious concord which would likely have alienated both Christian and Jewish authorities in antiquity. Despite its contemporary focus, however, Dabru Emet recognizes that Jews and Christians have been inescapably entangled for two millennia. This acknowledgment of profound enmeshment constitutes one reason why I, a rabbi with a Ph.D. in the History of Judaism, found myself not only wanting to study materials from Early Christianity, but needing to do so. The ways we study Late Antiquity—even in its nomenclature, which encompasses Patristics and Rabbinics, among other categories—reflects a distinctive facet of modernism, the moment to which Dabru Emet speaks.

Until quite recently, scholars of Judaism and Christianity in Late Antiquity were separated not only by canons of sacred and authoritative literatures to be mastered but the very languages in which those texts were written: Hebrew and Aramaic in Rabbinics; Greek, Latin, and Syriac in Patristics. In graduate school, one would specialize in acquiring the skills to analyze (for example) the Talmud or post-Nicaean Fathers. A well-rounded scholar in either field would ideally possess facility in the Bible (Hebrew Bible and Greek New Testament) and the Greco-Roman canon, but the curriculum inevitably emphasized those works most invested in articulating community boundaries. Academic training reinforced the impression or assumption that each community evolved largely in parallel, with friction or conflict occurring when they did intersect.

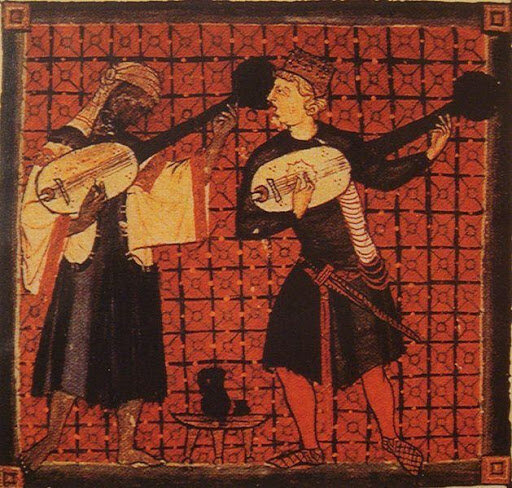

Christian and Muslim playing ouds. Catinas de Santa Maria, by King Alfonso X. (Public Domain).

Close readers of formative Jewish and Christian texts, however, long noticed the affinities of these works for each other; certain commonalities were too striking to ignore. Scholars would note, if not always seriously explore, resonances between Christian and Jewish modes of exegesis (e.g., Origen and the rabbis on the Song of Songs); they might highlight images and motifs common to both canons, and perhaps posit a theory to explain the parallels; and, at the most granular, lexical level, they explored the abundance of Greek words and classical rhetorical tropes in Mishnah, midrash, and homilies, and along the way consider what such evidence suggests about education of Jews and Christians in this period. But whether analyzing literary works or discussing ritual practices, the language of “borrowing” or “dependency” would routinely privilege one community as “original” and “authentic,” thereby diminishing the other’s claims to creativity and agency. Meanwhile, less authoritative texts and practices—including pseudepigrapha, magical texts, folklore, and such—presented more entangled pictures of daily life, but were, in turn, more likely to be described (or dismissed) as syncretistic or reflective of the less-learned masses.

In keeping with twentieth century trends that favored complexity over simplicity and regarded received wisdom with skepticism (the same general intellectual disposition that created an opening for Dabru Emet), scholars of religion in Late Antiquity, particularly in the post-War period, began to reevaluate the conventional understandings and periodization. What had once been seen as an orderly transition from Temple-based Judaism to Rabbinic Judaism became messier, “common” Judaism(s), in which different parties (rabbis and priests, in particular) competed for or shared authority. Similarly, scholars began to more fully account for and articulate the implications of a more gradual, halting Christianization of the Roman Empire and the cacophonous complexity of emerging Christianities, East and West. An appreciation for the blurriness of boundaries and hierarchies within communities presaged renewed recognition of the complicated nature of interreligious relationships, as well. For all the top-notes of discord, the recovery of Late Antique pluralism and diversity let long-lost harmonies be heard.

Laura S. Lieber, Ph.D., is Professor of Religious Studies and Classical Studies at Duke University, where she directs the Center for Jewish Studies.