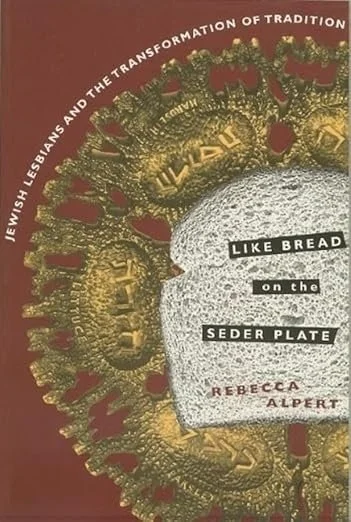

Like Bread on the Seder Plate

Rebecca Alpert

August 28, 2025

Like Bread on the Seder Plate: Jewish Lesbians and the Transformation of Tradition (Columbia University Press, 1997) was the result of a decade of writing and thinking about what it meant for me to come out as a lesbian rabbi and lose my job and standing in the Jewish community in the mid-1980s. While several important works by secular Jewish lesbians came before, it was the first work to tackle religious issues. The book’s goals were to wrestle with ancient texts, to raise consciousness about the presence of women who loved women and were hiding in plain sight throughout Jewish history, and to provide Jewish lesbians with rituals, midrash, and ethical precepts that would make possible our full inclusion in Jewish life.

The book succeeded beyond my wildest dreams. It got good reviews and was the centerpiece of my tenure case at Temple University, where colleagues praised it as being both accessibly written and rigorous in a scholarly way. Other authors built on what I started, creating life cycle ceremonies and midrashim, and highlighting historical evidence I uncovered. (For example, the banned lesbian-themed 1906 play by Sholom Asch, The God of Vengeance, has been produced multiple times in recent years.) My framing of a lesbian Jewish ethics based on the prophet Micah (to do justice, love loyally, and walk humbly) is still powerful and important for my own Jewish lesbian value system.

Like Bread is still in print and producing royalties. Just last month another colleague mentioned using it to positive reactions in her undergraduate classes, which has happened frequently over the years. I’ve also discovered it in published syllabi. To my great satisfaction I still meet people, young and old, who tell me how crucial my writing has been to them as they, or their family members and friends, were coming out in the Jewish world and sometimes in other religious contexts. In that way it has stood the test of time.

Perhaps most important, it played a pivotal role in liberal Judaism’s acknowledgement and acceptance of Jewish lesbians, welcoming us as couples and parents and as rabbis and educators, and incorporating our stories and rituals into Jewish life.

But success had other consequences. Like Bread is still a useful tool for understanding the changes in Jewish life necessary to make lesbians feel included. And it can still play a role for individuals who are struggling with coming out. But the widespread acceptance of lesbians in the liberal Jewish world has made its main argument, particularly the one reflected in its title, obsolete. It’s simply not likely that Jewish lesbians could feel as unwelcome as bread on a seder plate.

Despite its obsolescence, the title remains for me the most important thing about the book. In the course of my research, I heard two stories about Jewish lesbians being told unequivocally that Jewish and lesbian identities were irreconcilable. One instance was described in a Haggadah Jewish lesbians wrote at Oberlin College, where they described a “febrente rebbe” actually comparing their existence to putting bread on the seder plate. The other was a slightly gentler version where a rebbetzin speaking at a Hillel meeting in the Bay area was asked about being Jewish and lesbian. She modified the comparison to eating bread during Passover, a lesser sin but a transgression, nonetheless.

Of course, Jewish lesbians did not then begin to put bread on the seder plate in response. No matter how angry or hurt our exclusion and silencing had made us, our Jewish selves recoiled at the idea. So much so that when the book’s cover was being designed at Columbia Press, my editor could not find anyone who would contribute their seder plate to be used for the image. Instead, I loaned my own seder plate for the photo shoot. I treasure the beautiful cover that the designer created, respectfully using two separate images overlayed.

This was also the impetus for Susannah Heschel deciding to put an orange on the seder plate (representing all LGBT Jews who feel left out, so more inclusive and more benign). The orange has become as common as the olive, matzah of hope, and dozens of other symbols that broaden the scope of groups we want to recognize as needing liberation, and I’m proud to be part of that movement.

But there is also a distressing event that serves as a reminder of why the title is still meaningful to me. When I was invited to speak at a Reform synagogue for Pride Shabbat a few years ago, I was able to say unequivocally that the title of my book no longer applied, since Jewish lesbians were now welcome at the Seder table and the tradition had really been transformed by our contributions. But, I added, almost parenthetically, that I did still (and still do) experience being exiled from the organized Jewish community when I mention my pro-Palestinian/anti-Zionist views and my work in the Jewish Voice for Peace Academic and Rabbinical Councils. When I concluded the talk, the rabbi stood up and proclaimed that he never would have invited me if he knew about my Israel politics, sadly proving my point.

So the title still resonates for me. I share it with all Jews who even today feel like bread on the seder plate in any aspect of their lives, and I hope it brings them courage and inspires a commitment to work for change.