An American Joan of Arc

by Winnifred Fallers Sullivan

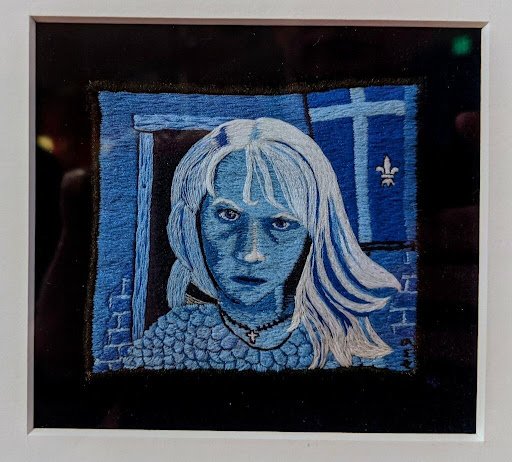

“Joan of Arc” by Ray Materson. American Visionary Art Museum, Baltimore.

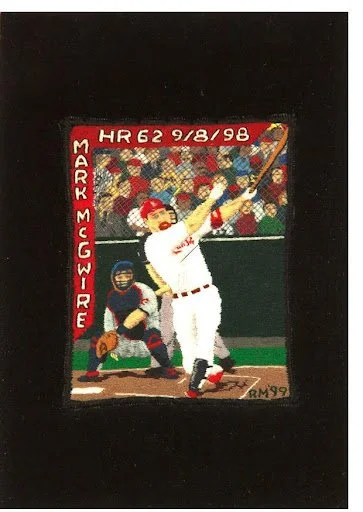

Ray Materson is an American artist who began to create embroidered images while he was in prison on a drug charge—a 25-year sentence of which he eventually served seven. His miniature art is made using thread from unraveled socks. Each image is about 2½ x 3 inches, with a stitch count of as much as 1200 per square inch. Above is a portrait of Joan of Arc made by Materson. He also embroiders baseball cards and a wide range of other themes. See, for example:

Materson explains his work in the following ways, online and in the short autobiography that he wrote with his wife:

I embroider. I embroider miniature images using the thread I glean from socks… Yes! Socks. I have collected a great many socks over the years and as long as they are there, I’m going to use them…call me a recycler if you will.

The work I create, the images, run the gamut from edgy, personal life images to portraits and sports—mainly baseball—art. I like to think of my embroideries as my job; strange though it may seem. But my job is really more than a means to put bread and butter on the table. It is through the artwork, through the creative process, that I continue to heal and reconstruct myself. There is always reconstructing that needs to be done. The art is my therapy in a manner of speaking. It keeps me centered and if I am away from it for too long, I get uncomfortable. I stress.

Here he is at home in 2007, captured from a news story about him:

As Materson tells it, his vocation came to him all of a sudden. Prison was a harrowing experience. One day a picture came to him of his grandmother embroidering on their front porch—a pool of calm in the midst of the chaos of their lives. He also remembered his childhood excitement of rooting for the University of Michigan teams—the blue and the maize. Casting his eyes around, he saw a pair of socks hanging on the bars of another cell, socks with UM’s colors. He then noticed a plastic Rubbermaid bowl whose opening was about the size of the embroidery hoop his grandmother used. As he explains, these memories and objects assembled themselves and thus, beginning with the UM logo, began his life-changing commitment to embroidered art.

Materson went to Catholic school as a child and thought of being a priest. At various points after high school, he belonged to churches—and he was substantially helped by a protestant pastor when he was in jail. He is at ease with God-talk. Some of his creations are explicitly religious in content, but many are not. It is the process that feels religious to him. The hours of intense concentration—the devotion—involved in their production. Their size—like the images of saints created for personal acts of piety. And his talk of transformation—of the materials and of himself. His tiny creations hang in museums now all over the world and are sold through art galleries. He speaks publicly for and of the world of mass incarceration.

I am writing a book about Joan of Arc. I find the many, many images of Joan, old and new, to be a bit overwhelming. We have no contemporaneous images of her. We have few descriptions of her physical appearances, and those we have are contradictory. Yet, as Materson’s image shows, only a few gestures are needed to invoke her—bobbed hair, armor, and a cross. Perhaps a fleur de lys. Or maybe you don’t recognize Materson’s blue portrait as Joan (without the label)? Maybe you have to be Joan-obsessed to see her in this tiny portrait? What is it that makes an icon?

I love Materson’s Joan. I love the blue. And the white. I love the circles under her eyes. I love the tiny precise stitches. I love the hair. I love her sad, knowing seriousness. She has work to do. And she is being thwarted.

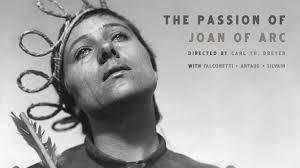

I also love its Americanness. What is it? The hair? The cross necklace? Her youth? Her seriousness? Unlike the well-known French equestrian and martial images of Joan—pious upholder of the monarchy—or even the mature knowing tears of Falconetti—

there is in Materson’s image an innocence. Not a child’s innocence but an American innocence. Direct. Democratic. Alone. Harrowed by the world she confronts. But brave in her innocence. And dangerous. The girl next door.

It seems highly transgressive—at best—to speak of American innocence today. Even offensive.

The offense is apparent in the story of another American Joan—at Marquette University in Milwaukee in 1996—whose burning was re-created during a conference about her, to the shock of bystanders who rejected the mimetic horror of the event and its unbidden references to racial and domestic violence. As the AP story about the event makes clear, the burning of a life-size effigy on campus in the middle of a city drew protests from the university black gospel choir, from faculty, and from passers by. (There is a Joan of Arc chapel on the Marquette campus, a medieval stone chapel brought from France and installed on campus at the expense of a donor. A stone in the chapel is reputed to be colder than others and to be one that Joan herself touched.)

Joan’s afterlives are many. Materson’s Joan is in prison, a scene from her life less often reproduced than the scenes of violence, of military triumph and martyrdom. Her intensity is not vengeful but inward. This is the Joan that was visited by voices. Quiet. Abandoned by her king and her church. Made of thousands of tiny stitches over many hours by a man whose life was turned around by sewing. His devotion offers her respect; his talk of healing and of the redemptive possibilities of prison referencing other deeply problematic American tropes conflating sin and crime.

Joan of Arc appears across the American landscape in popular media, as public art, as pious exemplar, gaming avatar, and nationalist hero. This tiny image of her shows, I think, her enduring capacity to exceed our efforts to hold her captive.

Ray Materson and Melanie Materson, Sins and Needles: A Story of Spiritual Mending (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books, 2002).

“Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” The Brooklyn Rail, August 11, 2020.

“From Jailbird to Embroidery Artist,” CBS Evening News, July 13, 2007.

Winnifred Fallers Sullivan, Prison Religion: Faith-Based Reform and the Constitution (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009).

Mary Elizabeth Tallon, ed., Joan of Arc at the University (Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 1997).

“Reliving Joan of Arc Death Sparks Protest,” Associated Press, October 15, 1996, updated January 10, 2011.

Françoise Meltzer, “Joan of Arc in America,” SubStance 32, no. 1, Celebrating Issue # 100 (2003): 90–99.

Winnifred Fallers Sullivan is Provost Professor in the Department of Religious Studies, Affiliate Professor of Law, Maurer School of Law, and Director of the Center for Religion and the Human. She is interested in religion as a broad and complex social and cultural phenomenon that both generates law and is regulated by law. Her particular research interest is in understanding the phenomenology of religion under the modern rule of law. Within legal studies, her work falls broadly within socio-legal and critical legal studies. She is the author of three books analyzing legal discourses about religion in the context of actions brought to enforce the religion clauses of the First Amendment and related legislation: Paying the Words Extra: Religious Discourse in the Supreme Court of the United States (Harvard 1994), The Impossibility of Religious Freedom (Princeton 2005), and Prison Religion: Faith-based Reform and the Constitution (Princeton 2009). Her fourth book, A Ministry of Presence: Chaplaincy, Spiritual Care, and the Law (Chicago 2014), portrays the chaplain and her ministry as a product of the legal regulation of religion and as a form of spiritual governance. She is also a co-author of Ekklesia: Three Inquiries in Church and State (with Paul Johnson and Pamela Klassen) (Chicago 2018) and a co-editor of three volumes, After Secular Law (Stanford 2011), Varieties of Religious Establishment (Ashgate 2013), and Politics of Religious Freedom (Chicago 2015).